An Interview with Fazal Sheikh

From Desert Bloom by Fazal Shiekh, Steidl, 2015

LATITUDE: 31° 21‘ 7” N / LONGITUDE: 34° 46‘ 27” E

October 9, 2011. Earthwork preparation for the planting of the Jewish National Fund (JNF) Ambassador Forest as part of its afforestation campaign to provide a green belt around the city of Beersheba (Heb., Beʼer Shevaʽ/Arabic, Bīr a-Ssabʽ). The JNF is a nongovernmental Zionist organisation founded in 1901 for the purpose of buying land, on behalf of world Jewry, for the foundations of a Jewish state in Ottoman-controlled Palestine. Today the JNF is active in afforestation and presents itself as a “global environmental leader.” In the summer of 2010, the homes of the Abu Jāber, Abu Mdīghem, and Abu Freih families, of the al-Tūri tribe, which were on the site surrounding the two remaining trees, were demolished, and the families expelled. The land is currently claimed by the Bedouin community as part of the surrounding area of the unrecognized village of al-ʽAraqīb.

Flipping through the pages of The Erasure Trilogy and The Conflict Shoreline, one encounters an Israel/Palestine strikingly dissimilar from the images we are normally swamped with by the international media. Although his position is manifestly that of an outsider, American photographer Fazal Sheikh’s photographs contain none of the cliché representations of the conflict. Our eyes are led, instead, to minute details: creases and wrinkles in a person’s face or in the bare desert land, patterns created both by nature and by human intervention.

For over twenty years, Sheikh has been photographing people from displaced communities around the world, exploring themes of exile and refugeehood. In the past, he has documented refugees in Kenya and Pakistan, and Mexicans crossing the US border. In a project on migrant labourers in Brazil, he has explored the connection between migrants and the lands they are forced to leave behind. Portraiture is a central feature of his work, which is often composed of both photographs and text, and published in book format alongside its exhibition in shows.

In his latest work, Sheikh documents his encounter with the people and landscapes of Israel/Palestine during visits he made between 2010 and 2015. The Erasure Trilogy, which includes Memory Trace, Independence/Nakba and Desert Bloom, explore the themes of loss and the preservation of memory. Desert Bloom, along with The Conflict Shoreline, a collaboration with architect and theorist Eyal Weizman, depicts the Negev, the desert region of southern Israel.

Generations of Israeli children have grown up hearing the mythical appeal to make the “desert bloom,” an exhortation made by Israel’s first prime minister, David Ben Gurion. Founded upon the conviction that the desert is an empty, barren stretch of land, waiting to be settled by Jews and transformed into fertile terrain, such Zionist mythologies effectively erase the presence of the Bedouin community – and the desert’s natural ecology – which has flourished for centuries. As Eyal Weizman describes in The Conflict Shoreline, for the last fifty years, the Israeli state has been expelling the Bedouins from their lands and resettling them in seven purpose-built townships located in more arid areas of the desert. The “unrecognised” villages of Bedouins who refuse to leave the land of their ancestors, such as al-Araqīb, remain disconnected from water and electricity supplies, and are repeatedly demolished. Al-Araqīb has now been razed over eighty times.

In conversation with Noa Levin, Sheikh shares his reflections on photography, the desert, and the fragile communities who struggle to inhabit it.

Noa Levin: What led you to this project and how did you come to visit Israel?

Fazal Sheikh: In 2010, I was invited to participate in a project called This Place (initiated by photographer Frédéric Brenner and displayed at the Tel Aviv Museum of Art, Israel and the Brooklyn Museum of Art, NY), which brought twelve photographers from around the world to Israel. The project was generous in the sense that it offered us the opportunity to stay six to ten months in the region and explore it in a manner which would let one’s preconceptions fade away and enable a more profound understanding of the issues. At first I was reluctant to participate in the project, because I was concerned about the possibility of being instrumentalised. I was also unsure I would be able to create something that was worthy of the project in its grand scope. But I was curious, and it was an opportunity to see the place in a way that I probably would not otherwise have been afforded.

I found my ability to move across the divide between the Palestinian and Israeli communities a rather interesting thing to pursue. Being offered hospitality by both communities is something that members of neither one of these communities could experience. My initial inquiry was about the legacy of 1948. I interviewed combatants from both sides of the war and what struck me as most curious was that so many elderly Israeli combatants would say, “You know, we grew up speaking Arabic.” One man in particular told me about a battle in Latrun, and after describing the nature of the battle, he suggested we visit the place to see the actual space where the battle took place. This got me thinking about the sites of the villages that had been formerly inhabited by Palestinians. I became interested not only in the ways in which those places have been transformed in the intervening years, but also in following the trajectory of those evicted from those villages to the places where they currently live in exile. As the villagers shared memories of the places they left sixty-five years ago, I soon realised I was functioning as a kind of conduit between the site of loss, the site of memory, and the current life in either a refugee camp or in the West Bank. This was, for me, compelling and fairly basic. I also found it interesting that the issue of 1948 and the events that led to the formation of the state of Israel continue to be a taboo subject within the country and that in many cases it seems a kind of provocation or affront to speak about the evacuated villages.

NL: And what led you to focus on the Bedouin community?

FS: Desert Bloom started with an invitation to travel to the south to meet with Haia Noach, who is the head of the Negev Coexistence Forum. With her, I visited the Bedouin village al-Araqīb, where I was able to listen to Sheikh Sayah al-Tūri, one of the leaders of the resistance to forced evictions. I think it was this encounter that led me to the project. This was just in the wake of a set of demolitions of the village and by that time the residents of the village were essentially living in the parametre of the cemetery. During the day they would meet in these kind of protest tents outside on the land where their homes had once been, and on which they had grown up. After hearing their descriptions of the cycle of demolition, it was very difficult to sit there and imagine what had been wrought upon the land. It suddenly seemed important for me to understand more about the context of where I was; what I was in the midst of; how the land was being transformed by Ben Gurion’s admonition to “make the desert bloom”; how that invocation had been used in the years since the start of the Israeli state; and what the southern part of Israel and the threshold of the desert looks like from above.

From Desert Bloom by Fazal Shiekh, Steidl, 2015

LATITUDE: 31° 12‘ 45” N / LONGITUDE: 35° 11‘ 60” E

October 4, 2011. Remains of Bedouin homesteads, south of Arad, near the unrecognized villages of al-Qurʽān and Qabbūʽa. Both Bedouin and Jewish local residents from Arad oppose a current government plan to establish a phosphate quarry on the site, stating health concerns including potential exposure to radioactive dust. The Bedouin settlement was evacuated when the Israeli military established a live-fire zone on the site, which will eventually be replaced by the mine. In winter people and livestock stayed within the enclosures on the lower slope and in summer they moved to the higher slopes. The earthwork enclosures below the dirt road that crosses from left to right were built by the Bedouins around places where their tents used to stand, for instance on the concrete floor within the gun-shaped enclosure on the left. The raised earthworks above the dirt road show traces of heavy mechanical equipment, which indicates that they are military enclosures for live- fire training. At top right a train of camels can be seen, led by one person.

NL: You have focused on portraits in the past. Did the shift to photographing landscape arise from this project?

FS: In some ways the landscapes are portraits in themselves. A portrait offers you a kind of invitation. It’s a kind of overture: it gives you some signifiers, some clues, and yet it doesn’t fully expound upon them. Landscape photography is similar. It doesn’t offer you all of what has been subsumed within the landscape, all the emotion and the history that is held within, but it provides an opening to begin engaging with a place. In my work, portraiture is often linked to testimony. You create a kind of resonance between the voice of the subject and what one is looking at, and hopefully those two, when they come together, make something that transcends the separate parts. Similarly, with the landscape, in particular with my aerial images of the desert, one may observe minute clues about what has transpired in that space.

Having realised the way in which the landscape has been transformed since 1948, I find it curious to see that the same kinds of modes of obfuscation that were used back then – attempts to cover up the acts of history that have impacted the space by way of afforestation, renaming/Hebraising, or by reframing – are still being used today, six decades later. For instance, if we talk about the Bedouin community – which we would perhaps consider as the most vulnerable community within the borders of present-day Israel – you can see those communities being eradicated and consolidated in townships established by the State in the Beersheba vicinity. In many cases, as in the case with al-Araqīb, the Israeli government, often in concert with the Jewish National Fund, then transforms the space by planting forests or nature preserves in place of the villages they raze. Consequently, if one were to return to the site of a former village twenty years down the line, one would be hard pressed to find any clue from what was there before. By using the overarching theme of environmental transformation, of making an inhospitable place livable (at least by Israeli standards) these demolitions become difficult to object to.

When you fly above the land, you see the fragile Bedouin communities carved out throughout the desert, which stand in stark contrast to the new, established settlements. You see two very different approaches to existence within that space. On the one hand you begin to recognise the tenuous existence that the Bedouins have lived over generations, and their ability to read the signs of the landscape, to harness what it has to offer during different seasons, and then to move on when the land isn’t offering what is necessary. And on the other, you can see a newer outlook upon the desert: the idea of making it conform to the state’s vision of a kind of hospitable, Western, well-tailored landscape we would like to live in.

NL: Was this the first time you have done aerial photography?

FS: Yes. I’ve never been particularly interested in taking photographs from the air, but it seemed to me a very clear step forward at the time. It felt necessary to make a foray up into the sky to see if it would be interesting, or somehow educative; to try and understand what was happening on the ground; to grasp the broader context of what this village – or former village – was experiencing at the threshold of the desert.

NL: I was wondering about what you can see from above, so high up, that you can’t see from the ground. On one hand it gives you perspective or context, but on the other hand you don’t see the people themselves. At a first glance it looks like the desert is empty, recalling the Zionist narrative which viewed the desert as empty, but on the other hand,when you look again you see traces of human life. Can you tell me more about the decision to photograph from such a distance, for example, in contrast to the close ups in Independence/Nakba?

FS: It was important for me to see the context of al-Araqīb within the broader scope of the way in which the desert has been transformed by the state. At the height at which I was flying you see basically everything on the land and you see it from a perspective which you cannot have when you stand on the ground. This vantage point offers a mode of seeing that renders visible the ways in which settlements, afforestation, and other kind of industrial areas are articulated on the landscape in a very strategic ways so as to consolidate the interests of one community over another.

From Desert Bloom by Fazal Shiekh, Steidl, 2015

LATITUDE: 31° 0‘ 60” N / LONGITUDE: 34° 43’ 4” E

October 9, 2011. Abu Asa family homestead in the vicinity of the recognized Bedouin town of Bīr Haddāj, of the ʽAzāzme tribe. The dark circular stains in the center of the image indicate the former presence of sire, livestock pens for camels, goats, and sheep. Staining is created by the bodily fluids of the herds that were kept there. Each year, the pens are shifted and the former space disinfected by fire. The stains remain on the ground for several years, the gradient of their saturation indicating how many rainy seasons have washed them away. Such traces help gauge the minimum duration of their presence in years. In 1978 Bīr Haddāj was declared a closed military area, forcing its inhabitants to relocate to Wādi al-Naʽīm, near Beersheba. In 1994, when they learned that land on which they had previously settled was no longer used for military purposes, but had been converted into a moshav, they returned and settled beside the moshav.

NL: Can you speak a little more about the ecological issues that the photos explore?

FS: In all four works, I explore the ways in which the rhetoric of environmental stewardship is used to justify transforming the land. Who can really argue against the idea of creating green areas, or making the desert fertile and habitable again? But what one really doesn’t often think about are the communities that are displaced during the course of those transformations. One should also ask how does one support the newly planted forests? How will they be sustained, and what aquifer is being depleted in order to to irrigate the desert? What happens when, after being irrigated for years, the salinity of the soil raises to an extent that the forest can’t be supported by the land anymore?

You have these extraordinary advancements in Israel in the way that tap irrigation has been developed to transform the desert. But it’s not certain what the long term implications of that kind of an incursion into the desert will be. This is what Eyal Weizman explores in the text that accompanies the photographs. As the title of our project, The Conflict Shoreline, suggests, we have a situation in which there are competing interests between those who attempt to force the desert back, and ecological changes that are causing the desert to push forwards against this kind of development, creating, as Eyal calls it, “conflicting shorelines.”

NL: What you say about the state using a rhetoric of environmentalism to justify its efforts to render the desert into a productive, "habitable" place, raises important questions about what is meant by "habitable”...

FS: That’s right – was it not habitable when the Bedouins were living there? Was it not of value that the Bedouin had – astutely, over time – found a way to live in a fragile harmony with the desert? Perhaps that’s a value judgment one has to make. Perhaps it is better to transform the space, to create a forest, and a settlement, and a township, and a massive military base. But, you know, I’m shying away from those value judgments because I want all three books to be a kind of invitation. The difficulty when you work in Palestine is that one feels a great sense of pressure to come down on one side of the divide, and be really assertive and aggressive in advancing your cause. And that’s not my sensibility, nor was that my desire. Rather, in all three books, I am more interested in looking at the cost of what that kind of strife has brought to the society and to the land, to history. Instead of trying to admonish, which I think really isn’t my place as an outsider, I’m trying to find a way to speak gently about the issues that touched me there.

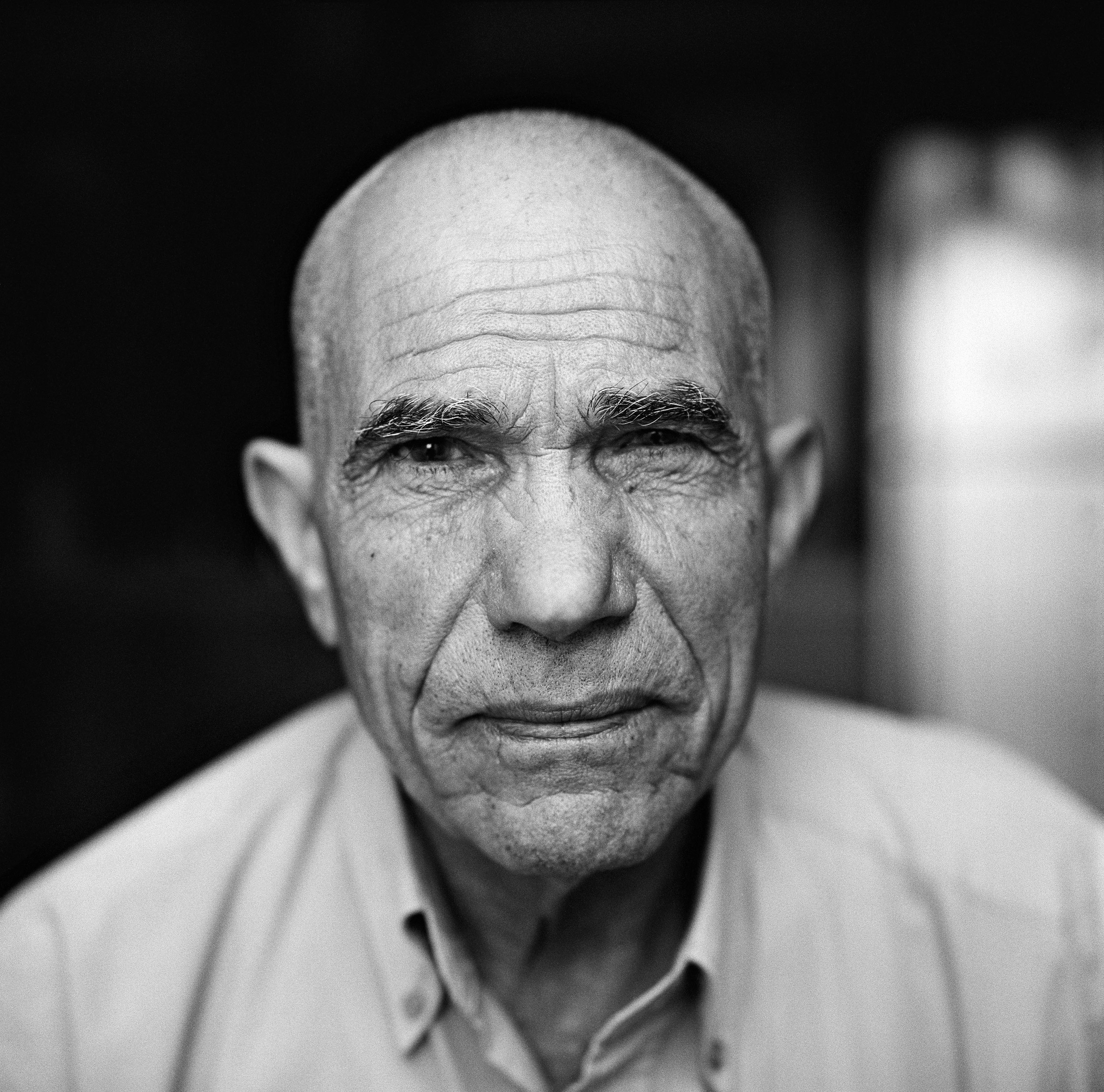

From The Conflict Shoreline by Fazal Shiekh and Eyal Weizman, Steidl, 2015

Nūri al-uqbi, Hūra

NL: In our conversation, and in The Conflict Shoreline, you and Weizman use the terminology of testimony or evidence. Do you feel that these photographs testify to something or can be used as evidence? I’m asking since The Conflict Shoreline recounts how aerial photographs were used in the courtroom, for example in the al-Uqbi vs. the State of Israel case, which resulted from six land claims Nūri al-Uqbi, a leader in the struggle for Bedouin rights, filed with the Beersheba District Court. As part of a report trying to prove ownership of the plots from which his family was repeatedly evicted, al-Uqbi submitted aerial photographs taken by the British Royal Air Force in 1945 as evidence to the court.

FS: In The Conflict Shoreline, a collaboration with Eyal Weizman, we looked at archival aerial images that were taken at a time in which the Negev was being flown over, both by the Bavarians in 1917 and by the British in 1945. We were searching for the remnants, or the facts on the ground, that would substantiate the idea of a Bedouin presence. Much of Eyal’s practice in general is about forensics. It’s about using evidentiary proof to substantiate claims. He’s looked very carefully at the archival images and has read the clues found in my images, so as to support a case for Bedouin existence in the desert. In that way, I hope that the images do support such a basic argument.

So yes, I think a large part of The Conflict Shoreline is a kind of investigation. It’s being offered to the Truth Commission, an initiative of the Zochrot organization which is talking about Israeli society’s responsibility for the way in which the Bedouin communities were handled in the early days of the state. I think that the commission is a really valuable and extraordinary endeavour, and I think that perhaps the part of it that resonates well with The Erasure Trilogy and The Conflict Shoreline is the idea that if one wishes to move forward in a generous fashion in a society, it’s important to acknowledge what has transpired in the past. Such a process was afforded the Israeli communities, those who had lived in the diaspora, this idea of basic testimony and acknowledging of the events of the past, and I think this kind of acknowledgment should be afforded to every community equally before one can begin to heal various wounds.

NL: Do you view your photographs as having a role in the preservation of the past, or of the present?

FS: I look at my photos at a variety of levels, one of which is honouring and memorialising what has happened in the past. Memory Trace, for example, focuses on an area in which former villages will be either completely subsumed by forests, demolished, or transformed into village annexes in the next few years. The former residents of these villages are 80-100 years old so they too will be dying off with such rapidity that there may no longer be a trace of the past left. So I don’t know what kind of evidentiary value a book like Memory Trace has for others. That’s not for me to determine. What is important for me is to at least honour the transformations that have taken, and continue to, take place.

NL: Desert Bloom, in which aerial photographs of the desert are printed on the entirety of each page, with no additional text, is accompanied by a booklet entitled Desert Bloom Notes, in which a miniature version of every photograph is accompanied by its longitude and latitude coordinates, and a short caption describing the landscape documented in the photograph and its history. How does this manner of presentation contribute to the idea of honouring transformations which have taken place in the land?

FS: The images I have made in Desert Bloom Notes are only markers in time. They’re largely from 2011, and if you utilise the coordinates, which are an important part of the caption, and look on Google Earth, you can see on the timeline how that the landscape has been transformed in the last decade. You can go back along the continuum to ten years before I took my pictures, and you can come right up to the present, so you can begin to see my photographs as markers along an expanse of time. So in one sense, they honour a particular moment in time, but in another, they are also only a pause along the continuum.

From Desert Bloom by Fazal Shiekh, Steidl, 2015

LATITUDE: 30° 48‘ 14” N / LONGITUDE: 34° 46‘ 19” E

October 9, 2011. Ancient walled farm, previously believed to be Nabatean but probably Byzantine (fifth century AD). The farm is made up of agricultural terraces within the bed of a seasonal stream. Ancient agriculture in the Negev, as well as the Bedouin agriculture that evolved from it, are based on the principle of "run off irrigation". Small terraces act as dams that channel and collect floodwater into irrigation basins, The water sinks deep into the soil and is stored there, rising to the surface over a long period. In an area with less then 100 millimetres per annum of rain, such irrigation systems could collect 4 times this amount and thus support cereal cultivation. There are thousands of Kilometres of such terraced wadis in the Negev. The small protrusions of earth on the slope at top left are ancient tuleilat al-ēnab (Arabic "grape mounds") The structure at the lower right would have been used for dwelling and storage.

NL: There’s an aesthetically pleasing aspect to the photographs, but then when you read the background story, which is violent and complex, a striking conflict is created. I was wondering if that was your intention.

FS: I think what’s interesting to me is this idea that when one first encounters the work sometimes you don’t know what’s there. Sometimes you may be lured by what you’re looking at, and then when you read the text there’s a kind of clash between what you read and what you see. This moment of rupture within your own mind is also breaking down a kind of barrier. And perhaps it also offers an opportunity to jostle, rethink, reimagine. When I looked at that picture why didn’t I understand what it was? Why did I find it seductive? And why, now, do I find it repellant? All of these things have already placed the viewer in a position of vulnerability and such a position is also a moment of consideration.

NL: The opposite approach would have been to show, for example, the demolition of the village, but here you use a very subtle approach, not showing the event itself, but only its traces or remnants.

FS: I think there’s value in working as an activist photojournalist, but what I’m interested in are things that contain a dynamism that moves beyond a one-sided reading of what is happening on the land.

NL: In The Conflict Shoreline your collaborator Eyal Weizman writes, “In these images the surface of the earth appears as if it was itself a photograph, exposed to direct and indirect contact, physical use and climatic conditions in a similar way in which a film is exposed to the sun’s rays. Sheikh’s aerial photographs must thus be studied as photographs of photographs.” I was wondering if that was something you identify with: the bareness of the desert being even more revealing in a way.

FS: What I like about Eyal’s reading of that set of images is this idea that there’s a particular time of the year wherein the land is opened up in such a way that, when seen from above, it reveals a lot of clues. That’s something that Eyal pursues extensively in his piece, this idea that if you catch the landscape there, at the right moment, you see clues that at other times of the year would not be visible. So the land becomes a kind of recording mechanism. I’m sympathetic to this reading, but what interests me the most is the idea of just witnessing what the land has to offer, whatever that may be. Whether it’s through obfuscation, or through subtle clues, it is a recording device. The kinds of clues the land offers can be read in a way which can be substantive evidence that might be used in a court or, as in the case of my images, they can be read, instead, as a trace of memory that honours a particular moment in time.

NL: Among the photos of Desert Bloom are some images of the remains of a fifth century AD Byzantine settlement. What went into the decision to include these traces of a far more ancient past?

FS: The images in Desert Bloom show you a vast expanse of history that stretches back to the very early habitation of this land. I wanted to provide a kind of perspective. In my work I am not just talking about the moment of transition that is taking place today. The project is not focused solely on the Bedouin issue. It’s also about a record, about the desert’s ability to record the traces on its surface through millennia. Some of the Byzantine villages were constructed in a fashion that allowed them to exert their imprint on the land over generations, while other villages, like those of the Bedouins, have erected structures that are easily wiped completely off the land. So they’re all in a dialogue. The idea of showing the historical imprints of the various transformations that the desert has undergone over the years – the various ways it has been lived in and moved through – was of great importance to me. This is a momentous time we are living in but there were many momentous times in the past.

To learn more about Fazal Sheikh's work, click here.